The Making of the Mahatma - M.K. Gandhi's Journey of Truth

I will give you a talisman.

Whenever you are in doubt, or when the self becomes too much with you, apply the following test. Recall the face of the poorest and the weakest man whom you may have seen, and ask yourself, if the step you contemplate is going to be of any use to him.

Will he gain anything by it?

Will it restore him to a control over his own life and destiny?

In other words, will it lead to swaraj for the hungry and spiritually starving millions?

Then you will find your doubts and your self melt away. [1]

I acquired this talisman as I neared the end of my visit to the Sabarmati Ashram–Gandhi’s home from 1917 to 1930–in Ahmedabad. I left with deep inspiration and curiosity and wanted to learn more about the formative influences that shaped Mahatma Gandhi into who he was. I remembered reading “Quotes of Gandhi” when I was younger. The depth of it was probably lost on me at the time. What drove his actions? What inspired his values? One could write endlessly about the Mahatma, but here’s a very brief glimpse into the stories, books, mentors and experiences that fed his soul.

Mahatma Gandhi’s life was a tapestry woven from early lessons in honesty, courage, and faith. Growing up in a devout household, he was exposed to diverse religious ideas, which created in him a real love for all religions. [2] From his boyhood in India, young adulthood abroad and return to India, Gandhi’s life was marked by a few defining moments. Here’s a short reflective journey through Gandhi’s life. We dive into the moments that planted the seeds of truth, service, and restraint that blossomed into his timeless legacy.

Honesty in the Classroom

One of Gandhi’s first moral tests came at school. As a shy student, Mohandas, nicknamed “Moniya” was “very fond of reading” [2] but academically unexceptional. On one occasion, an inspector visited his classroom and gave a spelling test. Gandhi misspelled the word “kettle.” Noticing the mistake, his teacher subtly nudged him to copy from a classmate. In that tense moment, young Mohandas quietly defied the hint. He later recalled that “the teacher tried to prompt me with the point of his boot, but I would not be prompted [3, Part I, Ch. 2]. Every other boy spelled all the words correctly, but Gandhi alone wrote “kettle” wrong – and he alone refused to cheat. The teacher scolded him for his “stupidity,” but Mohandas “never could learn the art of ‘copying’” [3, Part I, Ch. 2]. He left the class with a wounded spirit but an upright conscience. This is witness to the quiet power of integrity – the resolve to cling to truth even at personal cost. In later years, this seed of moral courage would grow into his conviction that Satya (Truth) is the most fundamental principle of life.

Legends of Truth and Devotion

As a boy two legendary figures from Indian lore—Shravana and King Harishchandra—deeply influenced Gandhiji. Gandhi first encountered these ideals through a book and a play during his childhood, and their impact was lasting.

Shravana’s Filial Devotion

One day, Mohandas picked up a play about Shravana, the son who carried his blind parents on a pilgrimage out of absolute filial devotion [3]. Shravana’s story comes from the ancient Hindu text Ramayana. Young Mohandas also saw a traveling theatrical picture of Shravana tenderly bearing his parents in two baskets slung on a yoke. The sight of Shravana’s selfless love left an indelible impression on his mind. “Here is an example for you to copy,” he whispered to himself, inspired to emulate Shravana’s reverence for his mother and father. This childhood resolve to be as caring and dutiful as Shravana nurtured Gandhi’s belief in respect and care for one’s parents and elders, and more broadly, a respect for duty and self-sacrifice in service of others.

King Harishchandra’s Vow of Truth

Around the same time, Gandhi obtained permission from his reluctant father to see a popular drama about King Harishchandra, a fabled ruler who appears in the Mahabharata and other ancient Indian texts. King Harishchandra sacrificed everything – his kingdom, his family, his comfort – rather than tell a lie. The play captured Gandhi’s heart; he watched it spellbound and “could never be tired of seeing it” [3, Part I, Ch. 2]. The story of a man who clung to truth through every hardship haunted young Mohandas. “Why should not all be truthful like Harishchandra?” he pondered earnestly, day and night. Harishchandra’s saga again ignited in Gandhi an almost sacred ideal: to live in truth no matter the ordeal. “To follow truth and to go through all the ordeals Harishchandra went through was the one ideal it inspired in me,” he wrote, noting that even years later “both Harishchandra and Shravana are living realities for me”. These legends taught the young Gandhi that truth and love were not mere abstractions, but qualities worth any sacrifice. The tears he shed for Harishchandra’s sorrows and Shravana’s devotion were, in a sense, the water that helped nurture Gandhi’s own moral convictions.

A Sacred Vow of Self‑Restraint

By his late teens, Mohandas had internalized many of these early lessons – honesty, piety, devotion – but life was about to test his commitment to them on a larger stage. In 1888, at age 18, Gandhi was preparing to travel to England to study law. His mother, Putlibai, worried about the moral pitfalls awaiting her impressionable son in the West: meat-eating, liquor, and lust were alien to their Hindu values. Unsure if Mohandas could withstand such temptations so far from home, she hesitated to let him go. To allay her fears, a family friend – a Jain monk named Becharji Swami – suggested that Mohandas take a solemn vow before departure [3, Part I, Ch. 11]. In a small ceremony, young Gandhi pledged not to touch wine, woman and meat while abroad. “He administered the oath and I vowed not to touch wine, woman and meat. This done, my mother gave her permission,” [3, Part I, Ch. 11] Gandhi recounted of that poignant moment

This promise was far more than a formality – it was a personal oath of discipline and self-restraint that Gandhi honored scrupulously during his three years in England. Surrounded by new influences and freedoms, he kept to his vegetarian diet, shunned alcohol, and held fast to the moral compass set by his vow. Gandhi’s vow to his mother instilled in him the principle of brahmacharya, or self-control, which later became a cornerstone of his life philosophy.

In England, Gandhi met Dr. P. J. Mehta, who humorously taught him European etiquette. “Do not touch other people’s things. Do not ask questions… do not talk loudly. Never address people as sir …” [3, Part I, Ch. 13] [4]

He learned that true freedom comes not from indulging desires, but from mastering them. This early exercise in restraint fortified his will and kept him aligned with his values, proving to himself that integrity means consistency between one’s principles and actions, even when far from the watchful eyes of home.

“Unto This Last”: A Book that Changed His Life

Not all of Gandhi’s formative influences were rooted in childhood or Indian tradition. In his young adulthood, he found inspiration in the unlikeliest of places – a book by a 19th-century English social thinker, John Ruskin. In 1904, while working as a lawyer in South Africa, Gandhi happened upon Ruskin’s Unto This Last – a powerful critique of industrial capitalism and a call to honor the dignity of every human being [5]. A friend had given Gandhi the book to occupy him on a long train journey, and Gandhi later described how “the book was impossible to lay aside, once I had begun it. It gripped me… I could not get any sleep that night. I determined to change my life in accordance with the ideals of the book.” [3, Part IV, Ch. 95]

The teaching of Unto This Last I understood to be:

1. That the good of the individual is contained in the good of all.

2. That a lawyer’s work has the same value as the barber’s inasmuch as all have the same right of earning their livehood from their work.

3. That a life of labour, i.e., the life of the tiller of the soil and the handicraftsman, is the life worth living. The first of these I knew. The second I had dimly realized. The third had never occured to me. Unto This Last made it as clear as daylight for me that the second and the third were contained in the first. I arose with the dawn, ready to reduce these principles to practice. [3, Part IV, Ch. 95]

Ruskin’s words struck a deep chord. Gandhi felt as if Unto This Last articulated truths already latent in his heart. “I discovered some of my deepest convictions reflected in this great book of Ruskin, and that is why it so captured me and made me transform my life,” he wrote. The effect was indeed “instantaneous and practical” – Gandhi was so inspired that he immediately made changes to his lifestyle and work. He scaled down his personal needs, embraced a simpler life in community, and translated Ruskin’s book into Gujarati under the title Sarvodaya (Welfare of All), spreading its message among Indians

Unto This Last convinced him that all work was equal and important, so long as it was honest work for the community. This idea of the equality of labour and the ethic of service became a bedrock of Gandhi’s social philosophy. The night he spent awake reading Ruskin was, in hindsight, a turning point – a quiet transformation in which an Englishman’s prose revitalized an Indian’s purpose.

Tolstoy, and the Power of Love

Around the same period, Gandhi’s moral and spiritual philosophy was further shaped by the ideas of Leo Tolstoy and the teachings of ancient Indian scriptures. In Tolstoy – the great Russian novelist and Christian moralist – Gandhi found a kindred spirit preaching the gospel of love, nonviolence, and soul-force. He read Tolstoy’s The Kingdom of God Is Within You [6] while in South Africa, and it profoundly affirmed his faith in ahimsa (nonviolence). Gandhi was in the midst of campaigning for Indian rights in South Africa when Tolstoy’s writing provided intellectual and spiritual validation for nonviolent resistance. Indeed, “his early hesitances about nonviolence were overcome by reading Tolstoy’s The Kingdom of God Is Within You”, which helped Gandhi see nonviolent love as a force stronger than violence [7]. He was so impressed with Tolstoy’s vision of meeting hatred with love that he later named his communal farm in South Africa “Tolstoy Farm” in honor of the Russian sage.

Gandhi observed that “Leo Tolstoy’s life has been devoted to replacing the method of violence… by the method of non-resistance to evil. He would meet hatred expressed in violence by love expressed in self-suffering.” This alignment of Tolstoy’s philosophy with Gandhi’s own ideals of satyagraha (truth-force) gave him confidence that his path of nonviolent struggle was on the side of timeless truth. It was as if Tolstoy’s writings provided a moral echo, spanning continents and cultures, reassuring Gandhi that love in action (through self-sacrifice and non-violence) is the surest way to overcome injustice.

Another significant work by Tolstoy, Letter to a Hindu [8], offered powerful insights into the nature of resistance and oppression, which resonated with Gandhi’s own experiences. In this letter, Tolstoy condemned the use of violence as a means of achieving political ends, urging the oppressed to resist evil not with force but through love and non-resistance. He argued that the Indian people’s submission to British rule was not due to their oppressors’ power, but because they themselves had accepted violence as a method of conflict resolution. Other notable but lesser known works by Tolstoy, such as What Shall We Do? [9], also explore themes of Christian ethics and social reform. Tolstoy’s perspective echoed Gandhi’s growing belief that true liberation comes not from resisting evil with more evil, but through the transformative power of love and nonviolence.

Indian Scriptures and Spiritual Heritage

In London, far from home, Gandhi turned to the Bhagavad Gita and found in its verses a wellspring of guidance. The Gita’s teachings of disciplined action, devotion, and equanimity resonated with him deeply. He began each day reciting its Sanskrit verses and pondering their meaning, a practice that continued into his time in South Africa [7]. Gandhi came to regard the Gita as “a great religious book, summarizing the teaching of all religions”, interpreting it not as a call to arms but as an allegory for the inner battle against injustice and untruth. Its ideal of nishkama karma – selfless service without attachment to results – reinforced his commitment to service and sacrifice [10].

Alongside the Gita, Gandhi was influenced by other sacred texts and figures: the teachings of Jainism (with its strict principle of non-harming), the compassion of the Buddha, the Sermon on the Mount [11] from the Christian Bible which he said “delighted him beyond measure” in its message of turning the other cheek [7], and the lives of saints and reformers from his own Hindu tradition.

All these rich sources of wisdom and faith converged to shape the moral outlook of the young Gandhi. By the time he returned to India in his early 40s, Mohandas Gandhi had distilled these influences into a personal creed centered on Satya (Truth), Ahimsa (non-violence), self-discipline, and service to humanity – the very values that would soon guide India’s struggle for freedom.

Shrimad Rajchandra: Gandhi’s Spiritual Mentor

Shrimad Rajchandra (Raychandbhai) was a profound spiritual influence on Gandhi. Meeting in 1891, Gandhi was struck by Rajchandra’s moral depth and spiritual insight, which guided him through moments of doubt. In the early 1900s, when Gandhi was uncertain about his faith while in South Africa, he wrote to Rajchandra with 27 spiritual questions. Rajchandra’s detailed replies resolved Gandhi’s doubts, strengthening his commitment to Hinduism [12][13]. Rajchandra’s teachings, especially through the Shri Atmasiddhi Shastra, deeply impacted Gandhi’s understanding of spirituality, particularly the principles of Satya (Truth), Ahimsa (non-violence), and Dharma (spiritual purity), which later shaped Gandhism [14][15].

Even after Rajchandra’s untimely death in 1901, Gandhi continued to draw inspiration from his letters. He regarded Rajchandra as the greatest influence on his spiritual life, often referring to him as the “best Indian of his times” [13]. Rajchandra’s guidance laid the foundation for Gandhi’s Satyagraha (truth-force) philosophy, which became the core of his non-violent resistance movement. The quiet Jain poet from Gujarat became the unseen hand moulding Gandhi’s inner life, nurturing the commitment to truth and non-violence that would define the Mahatma.

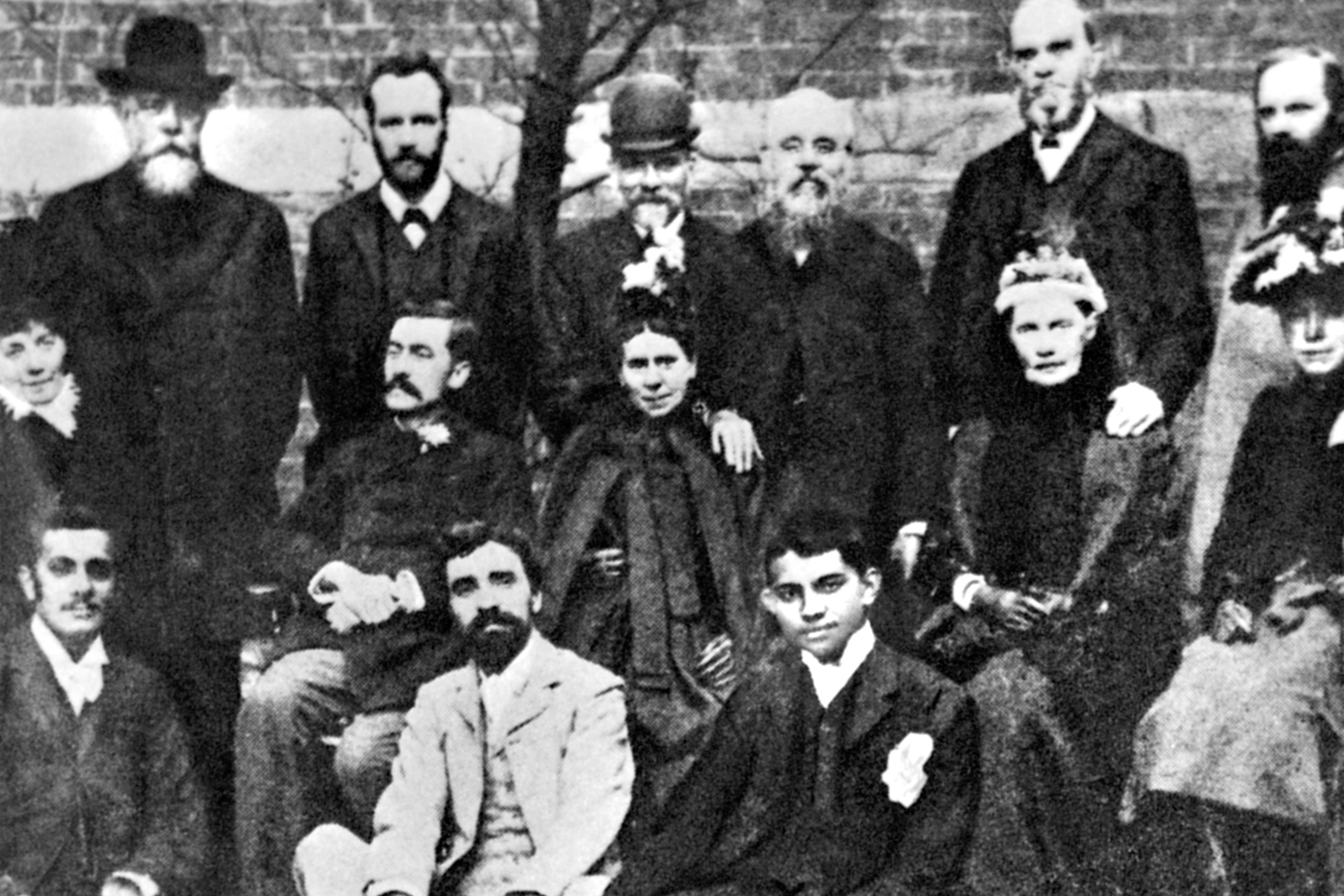

Gopal Krishna Gokhale: Gandhi’s Political Mentor

Gopal Krishna Gokhale was Gandhi’s political mentor, guiding him toward ethical leadership. Their first meeting in 1896 left a lasting impression on Gandhi, who felt an instant bond with Gokhale’s warmth and wisdom. Gokhale, a moderate leader, emphasized achieving self-rule through dialogue, social reform, and understanding India’s diverse realities. He encouraged Gandhi to travel India before diving into political action. Gokhale provided both moral and material support, helping fund Gandhi’s Sabarmati Ashram. Despite his untimely death in 1915, Gokhale’s influence remained crucial in shaping Gandhi’s leadership style, teaching him the importance of restraint, compassion, and ethical politics. Gandhi later honored Gokhale as his “political guru” and mentor, a figure whose values helped Gandhi lead India’s freedom movement [16].

Conclusion: Timeless Lessons for Today

Mahatma Gandhi’s formative years show that greatness is cultivated through everyday acts of conscience and courage. His schoolboy refusal to cheat teaches us that integrity is defined in small moments, while the stories of Harishchandra and Shravana remind us that ideals like truth, devotion, and love guide our actions. Gandhi’s vow of abstinence highlights the importance of personal discipline, and his encounter with Unto This Last reveals how a new perspective can spark a lifelong commitment to service and justice. His immersion in Tolstoy’s writings and the Bhagavad Gita demonstrates the value of seeking wisdom across cultures and ages.

Today, these lessons urge us to choose honesty, moral courage, and self-restraint over convenience. By serving others and practicing moderation, we recognize that our well-being is intertwined with the welfare of all. Seeking wisdom and living by enduring values can help us navigate the complexities of modern life.

Gandhi’s early journey challenges us to ask: How can we live out truth, love, service, and restraint in our own lives? The answer lies in our daily choices. Gandhi’s formative years remind us that greatness grows from the smallest seeds—a promise kept, a book’s insight, and the choices we make every day.

Modern Takeaway: Living Gandhi’s Early Lessons Today

Truth: Stand firm in honesty, even when a lie is easier.

Moral Courage: Do what is right in everyday situations.

Service: Help others and uphold justice, knowing your well-being is linked to theirs.

Self-Restraint: Practice moderation and master your desires.

Continuous Learning: Seek wisdom in literature, spiritual teachings, and noble lives.

These lessons invite us to become pilgrims of truth, growing through reflection, guided by conscience, and inspired by goodness.

References

[1] M. K. Gandhi, “Gandhi’s Talisman,” Ahmedabad, 1958. Available: https://www.mkgandhi.org/gquots1.php ↩︎

[2] Ramanbhai Soni, “The Story of Gandhi.” Available: https://www.mkgandhi.org/students/story1.php. [Accessed: May 04, 2025] ↩︎

[3] M. K. Gandhi, An Autobiography: The Story of My Experiments with Truth. Ahmedabad: Navajivan Publishing House, 1927. Available: https://www.mkgandhi.org/autobio/autobio.php ↩︎

[4] Satyagraha Foundation, “Formative Influences in Gandhi’s Life,” Satyagraha Foundation. Available: https://www.satyagrahafoundation.org/formative-influences-in-gandhis-life/. [Accessed: May 04, 2025] ↩︎

[5] J. Ruskin, Unto This Last. London: Smith, Elder & Co., 1862. Available: https://archive.org/details/untothislast00ruskuoft ↩︎

[6] L. Tolstoy, The Kingdom of God Is Within You. New York: Cassell Publishing, 1894. Available: https://www.gutenberg.org/files/43302/43302-h/43302-h.htm. [Accessed: May 04, 2025] ↩︎

[7] T. J. Rynne, Gandhi and Jesus: The Saving Power of Nonviolence. Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books, 2008. Available: https://books.google.com/books/about/Gandhi_and_Jesus.html?id=6OfNBgAAQBAJ. [Accessed: May 04, 2025] ↩︎

[8] L. Tolstoy, “Letter to a Hindu,” Nov. 19, 1909. Available: https://www.gutenberg.org/files/7176/7176-h/7176-h.htm. [Accessed: May 04, 2025] ↩︎

[9] L. Tolstoy, What Shall We Do? London: The Free Age Press, 2012. Available: https://www.gutenberg.org/files/38690/38690-h/38690-h.htm. [Accessed: May 04, 2025] ↩︎

[10] U. Majmudar, “Mahatma Gandhi and the Bhagavad Gita.” Available: https://www.mkgandhi.org/articles/Mahatma-Gandhi-and-the-Bhagavad-Gita.php. [Accessed: May 04, 2025] ↩︎

[11] The Holy Aramaic Scriptures, “Matthew 5 – The Holy Aramaic Scriptures.” Available: https://theholyaramaicscriptures.weebly.com/mat-5.html. [Accessed: May 04, 2025] ↩︎

[12] Shrimad Rajchandra Mission Dharampur, “About the Play Yugpurush – Mahatma na Mahatma,” 2017. Available: https://www.srmd.org/App/BookShow/Page/AboutThePlay. [Accessed: May 04, 2025] ↩︎

[13] S. Rajchandra, Shrimad Rajchandra’s Reply to Gandhiji’s Questions. Agas, Gujarat: Shrimad Rajchandra Ashram, 1894. Available: https://jainqq.org/booktext/Shrimad_Rajchandras_Replay_to_Gandhiji_Question/007522. [Accessed: May 04, 2025] ↩︎

[14] D. Jathar, “Indian who inspired Gandhi,” Jul. 16, 2017. Available: https://www.theweek.in/theweek/statescan/mahatma-gandhis-mentor-shrimad-rajchandra.html. [Accessed: May 04, 2025] ↩︎

[15] S. Rajchandra, Atma Siddhi Shastra. Umarala, Gujarat, India: Atma Siddhi Shastra Mission, 2015. Available: https://www.fulchandshastri.com/files/books/Atma%20Siddhi%20Shastra%20English.pdf. [Accessed: May 04, 2025] ↩︎

[16] R. Warkad, “Pune’s Gokhale House, home to Mahatma Gandhi’s guru and the Servants of India Society,” Pune, India, Mar. 17, 2024. Available: https://indianexpress.com/article/cities/pune/pune-gokhale-house-home-to-gandhis-guru-servants-of-india-society-9217643/. [Accessed: May 04, 2025] ↩︎