Ai Weiwei – Art, Activism, and the Rebel Spirit

Everything is art. Everything is politics.

This bold credo by Ai Weiwei – China’s most famous dissident artist – greets visitors to the Seattle Art Museum’s new retrospective Ai, Rebel: The Art and Activism of Ai Weiwei [1]. Across more than 130 works spanning four decades, the show reveals how Ai turns personal and political struggle into provocative art. He is celebrated worldwide as a disruptor of artistic canons and a champion of free expression.

But what shaped this rebel spirit, and how do his life and art ask us to rethink history, authority, and humanity itself?

Childhood in Exile: Foundations of Dissent

Ai Weiwei was born in 1957 to the renowned poet Ai Qing just as Mao Zedong’s regime denounced his father as a “rightist.” In 1958 the family was exiled to a remote desert outpost where they lived in an underground dug‑out to escape brutal heat and cold. For almost two decades they endured abject conditions: no electricity, water carried from afar, dirt beds, and a roof pierced for light [2]. Surrounded by rats, lice, and state hostility, young Ai learned “how vulnerable our humanity can be” [3]. That lesson became the bedrock of his identity as both artist and activist.

East Meets West: Inspirations and Influences

When China began opening in the 1980s, Ai seized the chance to explore the wider world. A decade in New York’s East Village introduced him to Western modernism; he abandoned painting in favor of readymades and conceptual provocations inspired by Marcel Duchamp and Andy Warhol [4], [3].

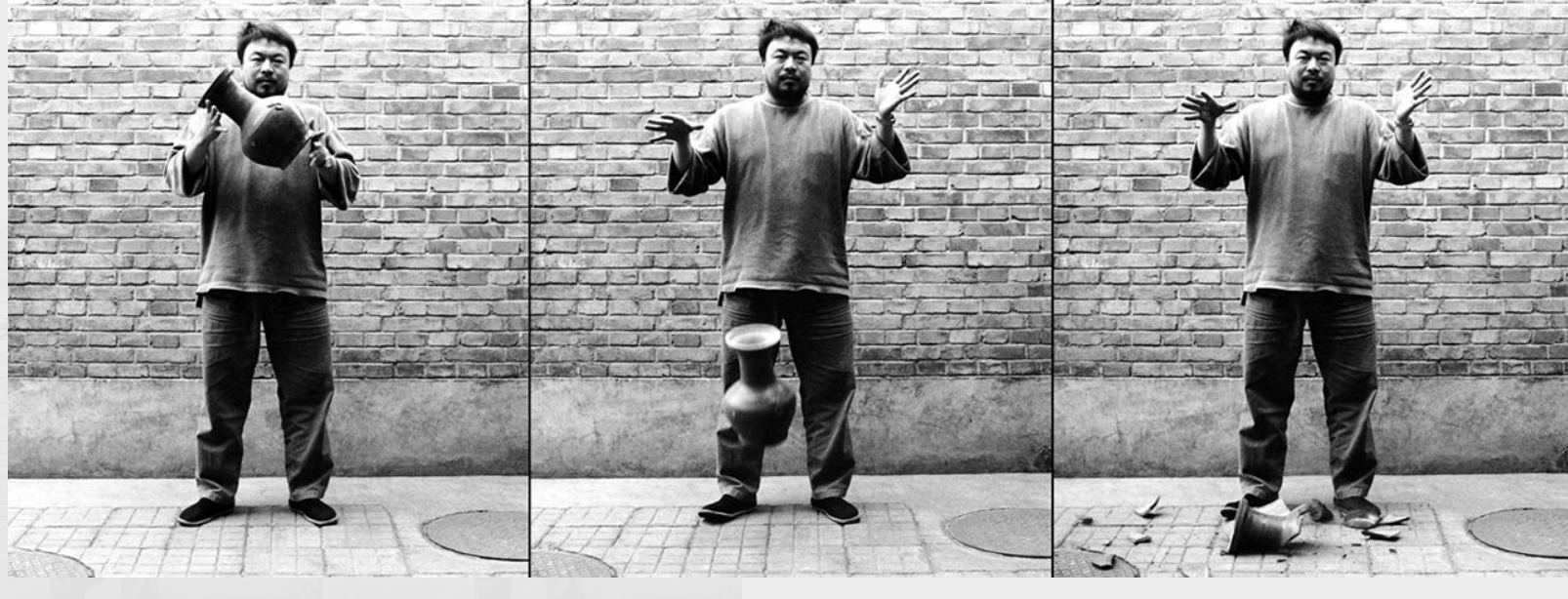

Yet his work is equally rooted in Chinese antiquity: he often repurposes centuries‑old wood or ceramics, forcing a dialogue between past and present [5]. A 2,000‑year‑old Han urn painted with the Coca‑Cola logo epitomizes this collision of eras [6], [7].

Art as Provocation: Iconic Works and Materials

- Sunflower Seeds (2010) – 100 million hand‑made porcelain seeds carpeted Tate Modern’s Turbine Hall, celebrating craft while critiquing mass conformity [8], [9].

- Straight (2008 – 2012) – 90 tons of Sichuan‑earthquake rebar painstakingly re‑straightened by hand, a memorial and an indictment [10], [11].

- Han Dynasty Urn with Coca‑Cola Logo (1993) – an ancient vessel reborn as pop‑art provocation [6], [7].

- Marble Sofa (2011) & Marble Chair (2008) – familiar household furniture recreated in monumental stone, freezing memories of family and exile [12], [13].

- Syrian Refugee Gate (2016) – a bullet‑scarred metal gate transplanted from a war zone to the gallery, forcing viewers to confront distant violence [4].

Confrontations with Power: Activism and Consequences

From citizen‑led name‑lists of Sichuan’s child victims to boycotting the 2008 Beijing Olympics, Ai has long used art as social sculpture [3]. His 81‑day secret detention in 2011 and four‑year passport seizure only amplified his global voice [14]. Photo‑series like Study of Perspective “flip off” power symbols worldwide [15], embodying his creed that “art is about bearing witness.”

Art in Exile: Films and Global Activism

Freed to travel after 2015, Ai turned to film:

- Human Flow (2017) – an epic survey of the refugee crisis [14].

- The Rest (2019) – a closer look at asylum seekers stranded in Europe [14].

- Coronation (2020) – an inside view of Wuhan’s COVID‑19 lockdown [4].

Conclusion

Whether porcelain seeds or straightened steel, Ai Weiwei’s materials insist that art and politics are inseparable. His work challenges us to remember the past honestly, to question authority fearlessly, and to act humanely in the present. As his father, Ai Qing, once advised: “The world is your home. You have to face it.” Ai Weiwei’s art shows us how. [16]

References

[1] Seattle Art Museum, “Ai, Rebel: The Art and Activism of Ai Weiwei,” Mar. 12, 2025. Available: https://seattleartmuseum.org/whats-on/exhibitions/ai-weiwei ↩︎

[2] “Ai Weiwei On His Father’s Exile — And Hopes For His Own Son,” NPR – Consider This, Dec. 30, 2021. Available: https://www.npr.org/transcripts/1068558765 ↩︎

[3] H. Sherwood, “Ai Weiwei: ‘It is so positive to be poor as a child. You understand how vulnerable our humanity can be,’” The Guardian, Oct. 30, 2021. Available: https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2021/oct/30/ai-weiwei-it-is-so-positive-to-be-poor-as-a-child-you-understand-how-vulnerable-our-humanity-can-be ↩︎

[4] “Ai Weiwei. In Search of Humanity – Albertina Modern,” The Stylemate, Mar. 16, 2022. Available: https://www.thestylemate.com/ai-weiwei-in-search-of-humanity-albertina-modern-bis-4-september-2022-2/?lang=en ↩︎

[5] E. Z., Sage, and Genevieve, “Ink Art’s Merging of the Old and the New,” The Metropolitan Museum of Art – Perspectives, Jan. 21, 2014. Available: https://www.metmuseum.org/perspectives/old-and-the-new ↩︎

[6] “Coca‑Cola Meets China: Ai Weiwei’s Subversive Symbolism,” Elephant, Sep. 02, 2020. Available: https://elephant.art/coca-cola-meets-china-ai-weiweis-subversive-symbolism ↩︎

[7] “Ai Weiwei, Dropping a Han Dynasty Urn, 1995,” Guggenheim Museum Bilbao – Teacher Guide, Jan. 15, 2025. Available: https://www.guggenheim-bilbao.eus/en/learn/schools/teachers-guides/ai-weiwei-dropping-han-dynasty-urn-1995 ↩︎

[8] Wikipedia contributors, “Sunflower Seeds (artwork),” Mar. 01, 2024. Available: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sunflower_Seeds_(artwork) ↩︎

[9] A. Searle, “Tate Modern’s sunflower seeds: the world in the palm of your hand,” The Guardian, Oct. 11, 2010. Available: https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2010/oct/11/tate-modern-sunflower-seeds-review ↩︎

[10] “What is Ai Weiwei’s Straight about?,” Public Delivery, Jul. 01, 2019. Available: https://publicdelivery.org/ai-weiwei-straight/ ↩︎

[11] M. Brown, “Ai Weiwei’s RA show to house weighty remnants from Sichuan earthquake,” The Guardian, Jun. 15, 2015. Available: https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2015/jun/15/ai-weiwei-ra-show-sichuan-earthquake-chinese-artist-steel-rods ↩︎

[12] D. Dailey, “All or Nothing,” Arcade NW, Apr. 13, 2025. Available: https://www.arcadenw.org/arc/all-or-nothing ↩︎

[13] “Sofa in Black,” Albion Barn & Fields, Jul. 09, 2023. Available: https://www.albionbarn.com/exhibitions/ai-weiwei-sofa-in-black/ ↩︎

[14] A. Wilkinson, “Ai Weiwei on the global refugee crisis, the Chinese movie industry, and his new film,” Vox, Jul. 22, 2019. Available: https://www.vox.com/culture/2019/7/22/20678786/ai-weiwei-interview-the-rest-human-flow-refugees-sheffield ↩︎

[15] Contemporary Art Curator Magazine, “Ai Weiwei, Study of Perspective Series (1995–2003),” Contemporary Art Curator Magazine, Jan. 29, 2016. Available: https://www.contemporaryartcuratormagazine.com/home-2/aiweiwei. [Accessed: May 02, 2025] ↩︎

[16] H. Ditmars, “Ai Weiwei’s Seattle retrospective is an exploration of human rights,” Wallpaper*, Mar. 24, 2025. Available: https://www.wallpaper.com/art/exhibitions-shows/aiweiwei-art-activism-seattle ↩︎